Book

Reviews

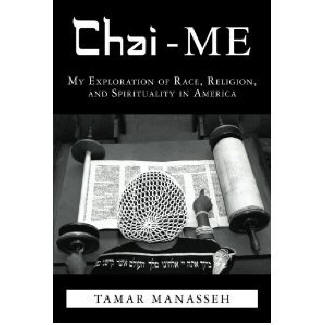

Chai-Me. Tamar Manasseh.

Chicago:

Createspace

Publishing,

2012. 138 pp.

Reviewed

by S.B. Levy

July

3, 2012

A new and promising writer

has emerged on the literary scene. Her name is Tamar Manasseh and her first

book is a very engaging memoir entitled Chai-Me:

My Exploration of Race, Religion, and Spirituality in America. The book invites comparison to such

classics as Toni Morrison's The Bluest

Eye and Richard Wright’s Black Boy in that it casts a light on the joys and challenges of being a

person of color in a world that views life primarily through the monochromatic

lens of white Christian society. What distinguishes this book within the genre

of African American literature and from the canon of Jewish autobiography in

general—both of which draw frequently on

themes of marginalization and estrangement—is that Manasseh tells her story

from the perspective of a woman who is both black and Jewish.

Refreshingly, Manasseh’s book

avoids the sense of victimization or cultural confusion that characterizes the

work of many authors who write about straddling the fence of multiple

identities. Although she vividly describes incidents of racism, anti-Semitism,

and sexism, Manasseh does not feel cursed by God for making her a black,

Jewish, woman; on the contrary, she feels thrice blessed. She finds harmony and celebrates the

beauty of each aspect of her being, rather than regarding them as inherently

contradictory elements that can only be held together by denying or

subordinating her race, religion, or gender. And while the focus of the book is

the interplay of these characteristics, she does not sacrifice the art of

telling a good story for bland truth-telling or dry of

sociological discourse. Here is an

example of how wonderfully her prose and ideas flow together:

They would approach me with this question like we were

running some kind of covert secret military operation. I’d be walking to my car

in the parking lot and a parent would pop out from between the cars, or they

might follow me to the neighborhood gas station or grocery store to question

me. It was done this way because I was not the black parent that other black

parents wanted the white parents and faculty to see them talking to. I was

black, but I wasn’t like them either. I didn’t have a college degree at that

time, I was young, much younger than the other parents, I

had just made 25, although I looked five years younger than that. I didn’t

drive a minivan or an SUV; I had a two-door sports coupe. I didn’t wear Dockers

and penny loafers with a natural hairdo. I was hood and they weren’t, or at

least they tried their best not to show it, but I was something else they

weren’t: a Jew. They had trouble understanding. They, educated black people,

would ask me question like: Is their father Jewish? Are they adopted? Or my

favorite, when did you covert? I felt sorry for them. These were people who

were by society’s standards successful. They were doctors, lawyers, and some

even taught at colleges and universities, but they had no idea that there was

such a thing as black Jews.

Manasseh writes from the

point of view of an Israelite (a term many black Jews prefer because it does

not connote a white European ethnic group) who grew up in a community of Black

Jews in Chicago even while attending and then sending her children to white

Jewish day schools. This is a heroic story of a women

who is comfortable in her own skin. She is fiercely proud of of the complexity of her identity and describes with great wit,

humor, and profound insight the process of making a place for yourself in the world as opposed to merely fitting into one

of the existing pigeonholes. This was the first book about black Jews that I, as

a black Jew, could identify with. In contrast to other books by people whose

journey to Judaism was the result of a bi-racial marriage, such as Rebecca

Walker’s[1] Black, White, and Jewish: Autobiography of a Shifting Self (2001),

or the consequence of a long search for identity, as in the case of Julius

Lester’s[2] Lovesong: Becoming a Jew (1988) and more recently Marcus Hardie’s[3] Black and Bulletproof: An African American Warrior in the Israeli Army

(2010). In these narratives the authors

were searching to find themselves; there was something incomplete or unsettled,

a void that Judaism filled.

Chai-Me, a title that could mean in

Hebrew “Whose Life?” or, with the double entendre that Manasseh probably

intends, “My Life.”

She calls this book the first volume of a much longer story she has to tell. It

may be best to consider it the first edition of one book that would be enhanced

by expanding on the topics covered and filling-in a few omissions that would

bring her life and people into even greater focus. Yet, even in its current

form, we have a book that sheds new light on what it means to be black and

Jewish from a black perspective. She takes us into black synagogues with black

rabbis and black schools. She also explains what it is like to navigate the

white Jewish world as a black person. To use a biblical analogy, Manasseh did

not sell her birthright like Esau, she struggled like

Jacob to become Israel. In other words, her journey is not a transition from

being black to becoming Jewish. It is not a transition at all. It is a

statement of being. Thus, we have a very particular story that has such

universal applicability that it can be enjoyed by anyone.

Purchase a copy today from Amazon :