Who are we? Where did we come from?

How many of us are there?

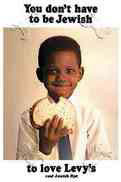

The above picture of a black kid eating a

slice of Levy’s Jewish Rye was a popular advisement that attempted to convey the

message that one does not have to be Jewish to enjoy Levy Jewish Rye. It did

this by showing a black person—who everyone knew could not be Jewish—eating a

sandwich made with this well-known Jewish bread. I don’t know how successful

this advertising campaign was at increasing sales for the sponsoring company,

but I do know that it had the effect of further embedding the stereotype that

black people are not Jewish; if fact, the very idea that they could be

contributed to the advertisement’s irony and subtle humor. Since I was a black

Jewish child whose name happened to be Levy, I understood this and similar

messages to mean that I did not exist or that my identity was not acknowledged.

Like Ralph Ellison’s classic novel Invisible Man, we became Invisible

Jews.

My story is typical and I invite others to

share their experiences of living in a world of complex identity with us on

various pages of this site. However, this essay is intended to bear witness to

true racial diversity that exists within the Jewish world. Though the focus is

necessarily on those communities that I am most familiar with, I attempt to give

a broader insight and offer some analysis of the unique dynamics that are at

work. It is also important to remember that not all of the groups mentioned here

accept the terms used to describe them. Some, in fact, reject the term "Jew"

precisely because it connotes, in the minds of most people, a white ethnic

group. Therefore, the use of this appellation could be misinterpreted as a

desire to be white or a denial of African heritage. In either case, its use here

could be regarded as an insult by some. The groups who feel this way prefer the

term Hebrew or Israelite because they believe it avoids a connection with

"whiteness," or conversely, implies a connection with "blackness." It is with

these two caveats concerning "race" that I use the term Jew as a de-racialized

description of people who are neither Christian nor Muslim but who profess to

worship the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. No offense is intended by my

choice of terms and I hope that none will be taken. Those who wish to register

their opinions about terminology and other matters may do so in the appropriate

discussion room on this site. I offer a fuller exploration of the page entitled

"The Racial Question" which can be found on the Hot Topics page.

Estimates for the total number of Black Jews in

America range from 40,000, reported by the Encyclopedia of Black America,

to 500,000 as stated in a feature story about Black Jews in Ascent

magazine. Unfortunately, none of the sources reveal how they arrived at their

figures.

The problem of determining a reliable estimate

of the number of Black Jews in America is made more complicated by the

difficulty of determining who is a "Black Jew." For instance, Arthur Huff Fauset

in his pioneering study, Black Gods of the Metropolis, used a

Philadelphia-based group called the "Church of

God" as the basis for a

chapter about "Black Jews." If one simply took an affinity with the Old

Testament and the observance of a few customs as a definition of being Jewish,

as do Fauset and others, then one's figures could be quite high; though very

inaccurate because they would count as Black Jews segments of what is usually

considered the Black Church.

On the other hand, if one used Orthodox Jewish

Law, called "Halackah," as the basis for defining who is a Jew, one would have

to know the religion of the mother of each person; because, by this law, one

cannot decide to be a Jew unless one's mother is a Jew. If the person or group

claimed to have converted to Judaism, then one would have to know if they

underwent certain rituals that involve the taking of special baths, (mikvot) and

in the case of a man, the symbolic pricking of his penis.

Halakhic Law offers a very precise definition

of who is a Jew. However, since fewer than ten percent of the 5.3 million white

Jews in America observe Orthodox Jewish Law, this standard cannot be applied to

Black Jews unequivocally, nor could I verify baths or pricked penises if I

wanted to. Yet, I am aware of a number of prominent African Americans and one

New Jersey congregation that have undergone formal conversion. This, too, is a

controversial issue about which there is much debate. We have created a page for

the free flow of opinions on this topic. In general, however, I believe that the

majority of our communities believe in a doctrine the Torah refers to as Shuvah,

the return of lost Jews to their original heritage. Recently, several leaders

within our community have advocated undergoing Halakhic conversion (as they

have) even though they believe in Shuvah. Their strongest argument seems to be

that it makes getting along with white Jews easier if you have such a

certificate rather than that it makes them feel more Jewish or brings them close

to Hashem (G-d).

My experience and the example of the Ethiopian

Jews now living in Israel—many of whom have been coerced into taking a

pseudo-conversion euphemistically referred to as “renewal”—reveals that the

legitimacy of these Halakhic conversions are frequently questioned depending on

which rabbi performed and most importantly depending on the race of the person

being converted; i.e. black converts are always more suspect than the

traditionally suspected white convert.

Since the particular Halakhic conversion

ceremony in use today is not found in the Torah, nor is it referred to in any of

the biblical instances where people joined the Hebrew faith, (Ruth for example),

we do not believe that it has the same legal weight as Torah law. Also, we feel

that it denies the concept of divine intervention and selection referred to in

Isaiah 11:11-12 and Jeremiah 3:14. In these passages the Hebrew prophets state

that God will be responsible for the gathering of His people which He shall

choose from the "four corners of the earth" and the from "islands of the sea."

This process is described as a selection of individuals rather than of groups,

"I will take you one from a city, and two from a family, I will bring you to

Zion." The fact that Orthodox rabbis hold that they are the sole arbiters of

deciding who is a Jew negates the existence or exercise of a divine will that is

not channeled through them first. In contrast, the ceremony we use serves as a

public acknowledgment of a spiritual transformation that has already taken place

within the individual.

Beyond this type of problem, however, there are

a number of political reservations that we hold regarding the way that people

are "accepted" into Judaism. The Halakhic procedures require recognition of and

acquiescence to Orthodox authority. Further, the Halakhic standard conflates

membership in a religion (a belief system or way of life accepted on faith) with

acceptance or approval of a particular religious body. An appropriate analogy,

that comes very close to describing our situation, is that the Pope or Catholic

Church can decide who is a Catholic but, he can not decide who is a Christian.

[The fact that some have tried notwithstanding.] Similarly, various boards or

councils may decide who is an "Orthodox Jew" for instance but they can not

presume to act as God in judging the content of a person's heart or the

sincerity of one's faith.

Judaism, as many of us understand and practice

it, is not a race. If it were, then no one could join it or leave it

without being genetically altered. Judaism is a creed; a living culture with an

ancient history. Those who practice it belong to communities that often have

unique traditions. Though it may not appear as such, most Jews belong to

definable communities which have traditions that come out of their own

histories. Sadly, some of the more influential communities attempt to exercise a

hegemony over the others. Black Jews generally reject the presumptive authority

of such groups—though they accept many of their traditions and interpretations

on other matters. Because of this, Black Jews exist on the margins of Jewish

society though well within the pale of principled disagreement.

Rather than inventing an arbitrary definition

or imposing a contested definition of Judaism onto the Black Jewish community, I

have chosen instead to discuss those groups that describe themselves as either

Black Jews, Hebrews, or Israelites. This approach will allow the reader to

understand how we. In this regard, I have found that a variety of very

interesting, complex, and still evolving notions of Judaism exist. It is my goal

to analyze the major theological, cultural, and political views that circulate

within these congregations in order to understand how they are informed by

issues of race, religion, and historical circumstances.

Rabbi W.A.

Matthew -- The Black Jews of Harlem

My background and most of my information comes from working with those

congregations that derive from the late Chief Rabbi Wentworth Arthur Matthew

(1892-1973). Rabbi Matthew founded the Commandment Keepers Congregation in

Harlem, New York in 1919. He trained

and ordained many of the rabbis who later founded synagogues in various places

of the United States and the Caribbean. Rabbi Matthew, it

turns out, was a close associate of Rabbi Arnold J. Ford who was the musical

director of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) which was

organized by Marcus Garvey in 1911.

The emergence of Judaism among people of African descent in the first half of

this century was made possible by a combination of the following factors: (1) A

strong religious tradition in the background of the person who became Jewish

that embodied Jewish practices from an early but unclear source. When

interviewed, many of the older members of this community recall memories of

their parents observing certain dietary laws, such as abstaining from pork or

salting their meat. Others recall traditions related to observing the Sabbath or

festivals such as Passover and Sukkot. In most cases these practices were

fragmentary and observed by people who simultaneously practiced Christianity.

The possible origins of these Hebraic

traditions could be traced to West Africa were a number of tribes have customs

so similar to Judaism that an ancient connection or maybe even descent from one

of the "ten lost tribes" is believed. Other possibilities for these

well-documented practices are through association with Jewish slave owners and

merchants in the Caribbean and North America. In this case,

the number of Jewish slave owners is known to have been small, yet it has been

shown that Jewish masters, particularly in the Caribbean, attempted to proselytize their slaves just as their Christian

counterparts had.. Therefore, the three main sources of Judaism for African

Africans today are: (1) Indigenous African Ancestry, (2) Conversion during or

after slavery, (3) Intermarriage between white Jews and people of African

descent, and (4) Shuvah, the conscious reclaiming of Judaism by people of

African descent whose ancestors were forced into Christianity.

Many African Americans who practice Judaism

today maintain that they have always had a close affinity with the Hebrews of

the Old Testament. This is true whether or not they recall particular rites that

remind them of the Jewish traditions they now follow. Scholars such as Albert

Raboteau have described in books such as Slave Religion that the biblical

struggles of the Hebrew people—particularly their slavery and exodus from

Egypt—bore a strong similarity to the conditions of African slaves and was

therefore of special importance to them. This close identification with the

biblical Hebrews is clearly seen in the lyrics of gospel songs such as "Go Down

Moses" and remains a favorite theme in the sermons of black clergy today.

What all this proves is that there was a foundation, be it psychological

, spiritual, or historical, that made some black people receptive to the direct

appeal to Judaism that Rabbi Matthew and others made to them in this century. If

black people were fertile ground for the harbingers of Judaism, then the

philosophy of Marcus Garvey was the seed that helped to bring it to fruition.

Put most simply, Garvey's message was one of Black Nationalism and Pan

Africanism. His goal was to instill pride in a people who were being humiliated

through institutionalized racism and cultural bigotry. Garvey and Matthew

attempted to challenge old stereotypes that either minimized a black presence in

history or the bible, or, that completely excised black people from these texts.

They argued that such distortions and omissions were harmful to the self-image

that many black people had of themselves. They debunked these myths by extolling the

contributions that black people made to the development of human civilization. To some extent this meant

focusing on the achievements of African societies such as Egypt and

Ethiopia in highly rhetorical and

romantic way. It also meant attacking the

false image that all the people in the

bible looked like Europeans. They

pointed out that by normative standards the dark hues of the ancient Hebrews

would cause them to be classified as black in today's world. This was

a revelation to thousands of black people who had previously accepted the all

white depictions without question.

Rabbi Ford and Rabbi Matthew took Garvey's

philosophy one step further. They reasoned that if many of the ancient Hebrews

were black, then Judaism was as much a part of their cultural and religious

heritage as is Christianity. In their hearts and minds they were not

converting to Judaism, they were reclaiming part of their legacy. This fit very

neatly with the biblical prophecies that spoke of the Israelites being scattered

all over the world, being carried in

slave ships to distant lands, and of being forced to worship alien Gods. (Deut

28)

Rabbi Matthew found himself in the peculiar

position of having to both justify his small following of black Jews in

Harlem, and also to explain the

presence of so many white Jews. His position on this subject went through

various stages. He always maintained that the "original Jews" were black

people-or at least not European; however, he did not deny the existence or

legitimacy of white Jews. In fact, as his services, synagogues, and attire show,

he deferred to orthodox conventions on many matters. For example, he maintained

separate setting for men and women, he used a standard Orthodox siddur (prayer

book) to conduct his services, worshippers wore tallitzim and kippot (prayer

shawls and yarmulkes), they affixed mezuzot, wore tefillin, used standard texts

in their Hebrew and rabbinic schools and read from a Sefer Torah.

Rabbi Matthew believed that although the

"original Jews" were black people, white Jews had kept and preserved Judaism

over the centuries. Since we, black Jews, were just "returning" to Judaism it

was necessary for us to look to white Jews on certain matters—particularly on

post-biblical and rabbinic holidays such as Hanukkah which could not be found in

the Torah. However, it is important to note that Rabbi Matthew felt free to

disagree on matters where he had a strong objection. He also recognized that

since many customs, songs, and foods were of European origin, that he had the

right to introduce some African, Caribbean, and American traditions into his

community. Of course, his right to do this was often challenged, sometimes by

Jews who had “Europeanized” Judaism in the past or who were "Americanizing"

Judaism in the present. Rabbi Matthew was constantly aware of apparent double

standards within Judaism. After decades of trying to find common ground with

white Jews by speaking at white synagogues around the county and at B'nai Brith

lodges internationally, and after repeated attempts to join the New York Board

of Rabbis, Rabbi Matthew concluded that black Jews would never be fully accepted

by white Jews and certainly not if they insisted on maintaining a black identity

and independent congregations. Since his death in 1973, there has been very

little dialog between white and black Jews in America.

The following diagram is a picture of how the

Black Jewish or Hebrew Israelite community is arranged. It shows the major

branches of thought, the largest denominations, and the particular breakdown of

the community founded by Rabbi Matthew.

Learn about other Black Jewish / Israelite

Communities in:

|

Israelite Board of Rabbis

Rabbi S. B. Levy, President

189-31 Linden Blvd.

Saint Albans, New York 11412

(718) 712-4646

info@blackjews.org

|

|

Contents |

|

Copyright 2007. No part of this

site may be copied or used without permission. If referring to information

on this site, keep all quotes in context and provide proper attribution to

its source. |

| |

Home |

|

| |

Exit |

|