Biography of Rabbi Arnold Josiah Ford

By

Rabbi Sholomo Ben Levy

Ford, Arnold Josiah (23 Apr. 1877-16 Sept. 1935), rabbi, black nationalist, and emigrationist, was born in Bridgetown, Barbados, the son of Edward Ford and Elizabeth Augusta Braithwaite. Ford asserted that his father’s ancestry could be traced to the Yoruba tribe of Nigeria and his mother’s to the Mendi tribe of Sierra Leone. According to his family’s oral history, their heritage extended back to one of the priestly families of the ancient Israelites, and in Barbados his family maintained customs and traditions that identified them with Judaism (Kobre, 27). His father was a policeman who also had a reputation as a “fiery preacher’ at the Wesleyan Methodist Church where Arnold was baptized; yet, it is not known if Edward’s teaching espoused traditional Methodist beliefs or if it urged the embrace of Judaism that his son would later advocate.

Ford’s parents intended for him to become a musician. They provided him with private tutors who instructed him in several instruments—particularly the harp, violin, and bass. As a young adult, he studied music theory with Edmestone Barnes and in 1899 joined the musical corps of the British Royal Navy, where he served on the HMS Alert. According to some reports, Ford was stationed on the island of Bermuda, where he secured a position as a clerk at the Court of Federal Assize, and he claimed that before coming to America he was a minister of public works in the Republic of Liberia, where many ex-slaves and early black nationalists settled.

When Ford arrived in Harlem around 1910, he gravitated to its musical centers rather than to political or religious institutions—although within black culture, all three are often interrelated. He was a member of the Clef Club Orchestra, under the direction of James Reese Europe, which first brought jazz to Carnegie Hall in 1912. Other black Jewish musicians, such as Willie “the Lion” Smith, an innovator of stride piano, also congregated at the Clef Club. Shortly after the orchestra’s Carnegie Hall engagement, Ford became the director of the New Amsterdam Musical Association. His interest in mysticism, esoteric knowledge, and secret societies is evidenced by his membership in the Scottish Rite Masons, where he served as Master of the Memmon Lodge. It was during this period of activity in Harlem, he married Olive Nurse, with whom he had two children before they divorced in 1924.

In 1917 Marcus Garvey founded the New York chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association [UNIA], and within a few years it had become the largest mass movement in African American history. Arnold Ford became the musical director of the UNIA choir, Samuel Valentine was the president, and Nancy Paris its lead singer. These three became the core of an active group of black Jews within the UNIA who studied Hebrew, religion, and history, and held services at Liberty Hall, the headquarters of the UNIA. As a paid officer, Rabbi Ford, as he was then called, was responsible for orchestrating much of the pageantry of Garvey’s highly attractive ceremonies. Ford and Benjamin E. Burrell composed a song called “Ethiopia,” which speaks of a halcyon past before slavery and stresses pride in African heritage—two themes that were becoming immensely popular. Ford was thus prominently situated among those Muslim and Christian clergy, including George Alexander McGuire, Chaplain-General of the UNIA, who were each trying to influence the religious direction of the organization.

Ford’s contributions to the UNIA, however, were not limited to musical and religious matters. He and E.L. Gaines wrote the handbook of rules and regulation for the paramilitary African Legion (which was modeled after the Zionist Jewish Legion) and developed guidelines for the Black Cross Nurses. He served on committees, spoke at rallies, and was elected one of the delegates representing the 35,000 members of the New York chapter at the First International Convention of Negro Peoples of the World, held in 1920 at Madison Square Garden. There the governing body adopted the red, black, and green flag as its ensign, and Ford’s song “Ethiopia” became the “Universal Ethiopian Anthem,” which the UNIA constitution required be sung at every gathering. During that same year, Ford published the Universal Ethiopian Hymnal. Ford was a proponent of replacing the term “Negro” with the term “Ethiopian,” as a general reference to people of African descent. This allowed the biblical verse “Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hand to God,” (Psalm 68:3) to be interpreted as applying to their efforts and it became a popular slogan of the organization. At the 1922 convention, Ford opened the proceedings for the session devoted to “The Politics and Future of the West Indian Negro,” and he represented the advocates of Judaism on a five-person ad hoc committee formed to investigate “the Future Religion of the Negro.” Following Garvey’s arrest in 1923, the UNIA loss much of its internal cohesion. Since Ford and his small band of followers were motivated by principals that were independent of Garvey’s charismatic appeal, they were repeatedly approached by government agents and asked to testify against Garvey at trial, which they refused to do. However, in 1925, Ford brought separate law suits against Garvey and the UNIA for failing to pay him royalties from the sale of recordings and sheet music, and in 1926 the judge ruled in Ford’s favor. No longer musical director, and despite his personal and business differences with the organization, Rabbi Ford maintained a connection with the UNIA and was invited to give the invocation at the annual convention in 1926.

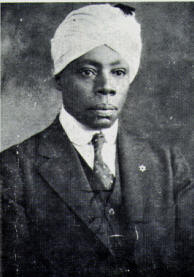

Several black religious leaders were experimenting with Judaism in various degrees between the two world wars. Rabbi Ford formed intermittent partnerships with some of these leaders. He and Valentine started a short lived congregation called Beth B’nai Israel. Ford then worked with Mordecai Herman and the Moorish Zionist Temple, until they had an altercation over theological and financial issues. Finally, he established Beth B’nai Abraham in Harlem in 1924. A Jewish scholar who visited the congregation described their services as “a mixture of Reform and Orthodox Judaism, but when they practice the old customs they are seriously orthodox” (Kobre, 25). Harlem chronicler James VanDerZee photographed the congregation with the Star of David and bold Hebrew lettering identifying their presence on 135th Street and showing Rabbi Ford standing in front of the synagogue with his arms around his string bass, and with members of his choir at his side, the women wearing the black dresses and long white head coverings that became their distinctive habit and the men in white turbans.

In 1928, Rabbi Ford created a business adjunct to the congregation called the B’nai Abraham Progressive Corporation. Reminiscent of many of Garvey’s ventures, this corporation issued one hundred shares of stock and purchased two buildings from which it operated a religious and vocational school in one and leased apartments in the other. However, resources dwindled as the Depression became more pronounced, and the corporation went bankrupt in 1930. Once again it seemed that Ford’s dream of building a black community with cultural integrity, economic viability, and political virility was dashed, but out of the ashes of this disappointment he mustered the resolve to make a final attempt in Ethiopia. The Ethiopian government had been encouraging black people with skills and education to immigrate to Ethiopia for almost a decade, and Ford knew that there were over 40,000 indigenous black Jews already in Ethiopia (who called themselves Beta Israel, but who were commonly referred to as Falasha). The announced coronation of Haile Selassie in 1930 as the first black ruler of an African nation in modern times raised the hopes of black people all over the world and led Ford to believe that the timing of his Ethiopian colony was providential.

Ford arrived in Ethiopia with a small musical contingent in time to perform during the coronation festivities. They then sustained themselves in Addis Abba by performing at local hotels and relying on assistance from supporters in the United Sates who were members of the Aurienoth Club, a civic group of black Jews and black nationalists, and members of the Commandment Keepers Congregation, led by Rabbi W. A. Matthew, Ford’s most loyal protégé. Mignon Innis arrived with a second delegation in 1931 to work as Ford’s private secretary. She soon became Ford’s wife, and they had two children in Ethiopia. Mrs. Ford established a school for boys and girls that specialized in English and music. Ford managed to secure eight hundred acres of land on which to begin his colony and approximately one hundred individuals came to help him develop it. Unbeknownst to Ford, the U.S. State Department monitored Ford’s efforts with irrational alarm, dispatching reports with such headings as “American Negroes in Ethiopia—Inspiration Back of Their Coming Here—‘Rabbi’ Josiah A. Ford,” and instituting discriminatory policies to curtail the travel of black citizens to Ethiopia.

Ford had no intention of leaving Ethiopia, so he drew up a certificate of ordination (shmecha) for Rabbi Matthew that was sanctioned by the Ethiopian government in the hope that this document would give Matthew the necessary credentials to continue the work that Ford had begun in the United States. By 1935 the black Jewish experiment with Ethiopian Zionism was on the verge of collapse. Those who did not leave because of the hard agricultural work, joined the stampede of foreign nationals who sensed that war with Italy was imminent and defeat for Ethiopia certain. Ford died in September, it was said, of exhaustion and heartbreak, a few weeks before the Italian invasion. Ford had been the most important catalyst for the spread of Judaism among African Americans. Through his successors, communities of black Jews emerged and survived in several American cities.

Further Reading

King, Kenneth J. “ Some Notes on Arnold J. Ford and New World Black Attitudes to Ethiopia,” in Black Apostles: Afro-American Clergy Confront the Twentieth Century, Randall Burkett and Richard Newman, eds. (1978).

Kobre, Sidney. “Rabbi Ford,” The Reflex 4, no. 1 (1929): 25-29.

Scott, William R. “Rabbi Arnold Ford’s Back-to-Ethiopia Movement: A Study of Black Emigration, 1930-1935,” Pan-African Journal 8, no. 2 (1975):191-201.