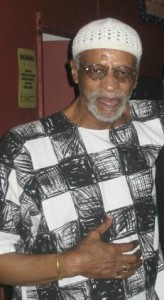

Cohen Levi Ben Yisrael:

His Life and Legacy

By

Rabbi Sholomo B. Levy

Cohen Levi Ben Yisrael was a founder of a unique group

within the Israelite community. As an intellectual he thought deeply

about the spiritual, political, and cultural doctrines that he helped to

define. As the leader of a congregation called Hashabah Yisrael he grappled

with the practical implications of turning beliefs into action over a period of

three decades spanning the 1960 through the 1980s. His legacy lives on in

congregations founded by his disciples. His particular school of thought as it

relates to the ways in which Black[1]

people should define their identity as Israelites is worthy of serious

attention. His experiences, contributions, achievements, and failures constitute

an important chapter in the ongoing story of how people of African descent reclaimed

their heritage as the chosen people of the God of Israel.

The man who would become known as “Cohen Levi” entered the

world as Irvin Steward Wanzer on May 27, 1927. He was born in Alexandria,

Virginia, to Irvin Steward Wanzer and Eloise Jones. His maternal grandparents, Samuel

and Maggie Jones, migrated to Virginia from South Carolina.[2]

The few people who knew Cohen Levi when he still carried the Germanic name

“Wanzer” say that he mocked the fact that such a European appellation was ever

attached to him as an example of how the true identity of Israelite people was replaced

by a European one. Never did he suggest that this Wanzer line might bear some

connection to Judaism as that idea would have been offensive and at odds with

the more powerful claim of direct descent from the Biblical Israelites who were

Black. Later, as Black nationalists embraced Egypt as an ancient African

civilization, Cohen Yisrael would joke, “Yes, I’m from Alexandria,–

Alexandria, Virginia.”[3]

By the age of twelve his family had moved to Harlem, New

York. He lived at W 112th Street with his mother and younger

siblings William (11), Doris (9), Richard (8), and Arthur (5).[4]

These were difficult years during the Great Depression. The Federal Census of

1940 lists his mother as being the married head of household who had been

unemployed for over a year. Young Cohen Levi attended school and was by all

accounts a very inquisitive and perspicacious young man. Yet, he must have felt

a great deal of pressure to help his family at an early age. By the age of

nineteen he married his first wife, Mary, with whom he had nine children. To

support his growing family he worked a variety of jobs, plied his talents as a

gifted singer, tended bar, and even considered joining the United States Army.

From the beginning he noticed that people were drawn to his charismatic

personality and he soon found himself the leader of a street gang called the

Seven Wise Men. As the name implied, they were not some mere group of hoodlums,

but a collection of young black men seeking direction and a higher calling.[5]

The first Black synagogue in the United States was founded

by Chief Rabbi W.A. Matthew in the year 1919.

It was called Commandment Keepers and it was a well-known fixture of the Harlem

community where Cohen Levi grew up. He did not join this congregation, but Cohen

Levi became a devoted acolyte of Rabbi Yirmeyahu Yisrael, one of Rabbi

Matthew’s students. Rabbi Yisrael, who was known as Julius Wilkins at the time,

started a congregation in Harlem called Kohol Beth B’nai Yisroel in 1945; it

was located at 204 Lenox Ave. The congregation followed the traditional Jewish

liturgy and used a standard Orthodox siddur (prayer book) to conduct its

services. Like all students of Rabbi Matthew, Rabbi Yisrael taught that the

original Jews were Black people. Conflict arose between Rabbi Yisrael and his

colleague Rabbi E.J. McCloud over cultural issues, particularly the

appropriateness of certain Black Nationalists songs that originated with Rabbi

Arnold Ford during the Marcus Garvey period and with certain Negro

Spirituals with Old Testament themes that remained popular with followers of

Rabbi Matthew. In 1954, Rabbi Yisrael started a new congregation called B’nai

Adath Kol Beth Yisroel. It was located briefly on 123 Street in Harlem, but

quickly moved to 131 Patchen Avenue in Brooklyn, New York. [6]

Cohen Levibecome a member of B’nai Adath in

1958 at the age of thirty-one. For the next six years B’nai Adath was Cohen

Levi’s home, his school, and the incubator for much of his later work. It was

at B’nai Adath that he studied Torah, learned about Israelite history, and

spoke Hebrew for the first time. Like Cohen Levi, all the original founders of

Hashabah came from B’nai Adath. From this same

rabbinic environment at B’nai Adath emerged many other congregations that on

their surface appear to be quite different but share the same origin such as Kol

Sheareit B’nai Yisrael, Bronx, New York and its offshoot, Kalutzeh Yisrael,

Bronx New York. If one began to count congregations started by the students of

these founders, the list would grow exponentially to include congregations such

as Sh’ma Yisrael, Brooklyn, New York,;

Hashabah Yisrael in Guyana, South America,; Hashabah Yisrael in

Baltimore, Maryland,;

Kwahal B’nai Yisrael, Brooklyn, New York, Kwahalet Mishpachah, Atlanta Georgia,

She’ar Yashuv, Atlanta Georgia,;

and most recently, Hashabah Yisrael Hebrew Family of Charlotte, North Carolina.[7]

People outside of our community are often so obsessed with

the racial politics or distracted by the music and dress that they completely

miss the deep spiritual core of our community. Consider what a typical Sabbath

day at B’nai Adath was like at that time. Worshippers would begin arriving at

about 10:00 in the morning. They would recite prayers in Hebrew and English

until about noon. They would then remove the Torah scroll from the ark and

carefully read the assigned portion, the same passages that Jews around the

world were reading on that day. The next hour following the Torah service was

given to the rabbi who would usually give a fiery sermon or erudite lecture.

This is the only part of the service were issues of race might be discussed. A

long recess for lunch would take place. Service would resume in the late

afternoon with the recitation of more prayers and songs until the early

evening. The congregation would then have Kiddush (reception) and light the

Havdallah candles at sundown signifying the end of the Sabbath. What this

reveals is that we spend most of our time talking to God and very little time

talking about race. It is because we are Black like the rabbi, cantor, choir,

and the majority of members in our synagogues that we can momentarily transcend

the racial awareness that is almost inescapable when you are the racial

minority, the racial outsider in a predominantly white synagogue. In our own

congregations we are able to elevate our spirits to a place that our bodies

can’t go. However, for us this is not a form of religious or emotional

escapism. The sermons teach people how to deal with life and the situations

people encounter. Often these are universal concerns such as family, marriage,

children, and work. However, the rabbi would be a negligent teacher indeed if

he ignored the elephant in the room, the racial barriers and historical

distortions that alienate Black people from their Israelite identity and

estrange them from their God.

Those who remember Cohen Levi as a young man at B’nai Adath

recall his sincere devotion as he wore a tallit and recited those prayers with

conviction. They remember his melodious voice as he chanted the Sh’ma and sang

Adon Olum. The transition that caused him to leave B’nai Adath occurred

gradually. As Cohen Levi studied Torah he and several associates, including his

hunting and fishing partner, Moreh Yosayf ben Yisrael, noticed that many of

their beliefs and practices were not based on scripture, but were rather

traditions created by European rabbis. They began to ask Rabbi Yisrael questions

like: “Where in the Torah does it say that we must light Hanukkah candles?” and

“Who says that we must say this blessing before eating bread and another

blessing before drinking wine?” Rabbi Yisrael, an old school Black Nationalist

himself, readily acknowledged that some of his practices were of European

origin but argued that they had value and meaning nonetheless. He also believed

that their observance fostered a sense of unity with the larger White Jewish

world. Such criticisms grew more frequent and more intense as they addressed

matters of Halakah (Rabbinic Law) that seemed to contradict or replace the laws

of God as they read them in the Torah. For example, God said that the festival

of Sukkot should be observed for seven days; most White Jews observe eight—as

they add an extra day to most festivals. Furthermore, the dietary laws

contained in Deuteronomy are very specific as to which foods are permissible

and which are forbidden. Rabbinic law greatly expanded the category of forbidden

foods to include all meat, fish, or poultry eaten at the same meal with any

dairy product. In many instances such as these Rabbi Yisrael and most rabbis of

the Israelite Board of Rabbis charted their own, independent, course between

Torah and Halakah.

By 1964 Cohen Levi Yisrael and his cohorts increasingly

perceived that a separation and absolute purging of all European traditions

was necessary. When Rabbi Yisrael publicly declared

that those who were not in agreement with his doctrine were free to leave, the controversial

contingent left B’nai Adath. This small band was led by Cohen Levi and Moreh Yosayf.

Even their titles signified a break with European tradition where the leaders

of synagogues are called rabbis. The Torah refers to the spiritual leaders of

the community as cohanim (priests) and moreh means “teacher” in Hebrew;

therefore, these were the titles they chose. The two men always taught together

and were so close in their conceptions of Torah that people dubbed them

“Prudence and Patience.”

For the first few months the fledgling congregation met in

each other’s homes and occasionally rented a masonic hall on Willoughby Avenue

in Brooklyn. During this period Cohen Levi and his family lived in the Astoria

Housing Projects in Queens, New York. As fate would have it, my family lived in

the same projects and my father, Chief Rabbi Levi Ben Levy, who was then a

young rabbi who had started a congregation in his living room called Beth

Shalom, occasionally rented the same masonic hall.[8]

My father and Cohen Levi would come to represent the polar

opposites of the Israelite world, but at this moment in time they lived in the

same place and they spent long hours talking, laughing, and arguing. I was so

young that those humble days when our families were close seem distant and far

away. Yet in later interviews with my father he discussed Cohen Levi with a

combination of affection for the love the man had for his people and regret

that they could not find a way to work together. My father tried to convince

Cohen Levi that the rabbinic approach to studying, thinking, and deciding

religious and communal issues was applicable to us. He urged him to consider

the centuries of learning and wisdom—much of it derived from our sages—that we

would lose if we “threw out the baby with the bath water” because we disagreed

on some points or simply because the person who wrote or preserved something

was White. As the Talmud says, “Who is wise? He who can learn from anyone.” Cohen

Levi responded passionately that we did not need anything from White Jews, that

they diverted us from the true pursuit of Torah, and most importantly that we

could create all the customs and traditions we needed. These conversations grew

heated and repetitive. Eventually the accusations became personal as Cohen Levi

suggested that leaders who incorporated rabbinic teaching as part of their

theology were on a hopeless quest to gain acceptance from White people because

deep down they wanted to be White.[9]

Hashabah Yisrael came into existence in 1965. Among the charter

members were Moreh Yosayf, who was listed as the president on the papers of

incorporation, Professor Y’sudah Yehudah, his wife at the time, Brother

Bakbakkar Yehudah, Brother Meshullam and Geveret Miryom Baht Yehudah, who was

the secretary of the congregation and the first wife Cohen Levi had taken after

he sanctioned the Biblical practice of polygamy. Eventually, Cohen Levi would

take three additional wives: Geveret Hadassah, Geveret Keturah, and Geveret

Rivkah.[10]

Moreh Yosayf left the group soon after it had formed to start his own

congregation, Kol Sheareit B’nai Yisrael (Remnant of the Children of Israel) in

the Bronx. Professor Y’sudah remained a member of Hashabah, became its assistant

treasurer and ultimately its secretary of more than twenty years. She edited a

newsletter along with Cohen Levi’s wife, Miriam, which was named TUF (Truth,

Unity and Freedom). They co-led the women’s organization – Nashe Binah – along

with a third female member of the congregation named Besemah Benyamin.

It was during this time that Cohen Levi had his first

fortuitous meeting with Ben Ammi, an Israelite leader from Chicago who was

visiting New York. Both men had similar ideas. They advocated a break from

Jewish traditions, embraced an Afrocentric Israelite culture, reinstated

polygamy, and spoke of one day returning to our ancestral land of Israel. It

seems that the subtle differences that prevented them from forming an alliance

was the perception that Ben Ammi had not taken his followers out of

Christianity; but rather fused New Testament doctrine—including messianic

beliefs about himself—with his definition of what it meant to be an Israelite. Cohen

Levi and his followers rejected Jesus and the New Testament even more strongly

than they opposed European Judaism. Christianity was deemed idolatrous. They

wanted to restore the Nation of Israel to what they imagined it to be before

Christianity and before European influences.[11]

When Hashabah Yisrael acquired its first home on Gates

Avenue in Brooklyn and began holding regular services, Cohen Levi had to

establish the substance of his alternative to Judaism. This was not an easy

task. He had to create an entire liturgy for conducting Sabbath services, festivals,

weddings, funerals, etc. He assembled his own prayer book which consisted of

psalms, passages of scripture, and a few beautiful prayers that he wrote

himself. Always a gifted singer, he composed songs in Hebrew and English to

replace the Jewish hymns and Negro spirituals. His most popular song is called

“What’s My Name?” Cohen Levi explained that the inspiration for this song came

to him one evening as he was riding on a New York City subway car. He looked

around at the Black passengers and pedestrians and thought to himself, “most of

these people are so lost that they don’t even know their true names.” He wanted

them to know that they are not Negroes, but the people of the Bible, the dry

bones of Ezekiel, the scattered House of Israel.

Cohen Levi was not alone in his search for an authentic

Black identity. This was the height of the Black consciousness movement of the

1960s. Black Nationalists such as Amiri Baraka and Mulana Karenga were

advocating many of the same things—except without the Torah. Black people all

over the country were wearing Afros and dashikis. The radicle Brooklyn

community activist Sonny Carson and Cohen Levi were good friends. There is even

a picture featuring Cohen Levi and Rabbi Levi Levy together on a panel with the

actor and activist Ossie Davis during a community meeting to discuss the

condition of public schools in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville section Brooklyn.

Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam made the same appeal as they tried to

persuade Black people that they were truly Muslim.

At first members of Hashabah rid themselves of the

cookie-shaped yarmulkes that Jews wore on their heads and replaced them with knitted

or crochet head coverings; they also wore West African garb with the addition

of tzit tzit (fringes) on the corners of their garments. They seemed to be

aware that their West African attire did not match the eastern garb that

Israelites wore in Biblical days. Slowly they began to adopt the turbans and

long robes that had become the hallmark of a rival Israelite group called B’nai

Zaken founded by Prince Yaakov and Navi Tate.[12]

According to some accounts, Cohen Levi appropriated Hashabah’s dress code and

the use of African drums from B’nai Zaken which was located on Buffalo Avenue

in Brooklyn. Other people argue that some undisciplined members of B’nai Zaken

considered their unique dress to be the equivalent of gang colors; therefore,

no one who was not a member of B’nai Zaken should be allowed to dress like them.

A very frightening turban war existed between Hashabah and B’nai Zaken for quite

some time until tensions subsided.[13]

Although Hashabah and B’nai Zaken had a similar dress code,

Cohen Levi introduced some practices that distinguished his organization. He

instituted a priesthood that roasted lambs during Passover and introduced the

baking of matzote by his members. They also accepted offerings of bread baked

during Shavuot and offerings of fruit during Sukkot. His priests also blewsilver trumpets—all rituals that the ancient Levites

performed at the temple in Jerusalem. In contrast, B’nai Zaken created new

offices and introduced some new terminology into the Israelite lexicon. Based

on passages in the Torah from the books of Numbers and Deuteronomy, where Moses

organized the slaves of Egypt into the army of Israel, they organized

themselves in a paramilitary manner. Hence, their leaders carried the title

“prince,” “chief,” or “captain.”

As the congregation grew it found larger quarters on Belmont

Avenue where it flourished for most of the 1970s. Geveret Miriam labored

tirelessly along with parents and members to establish a Hebrew school for

their children – the Israelite Institute. Various auxiliaries for men and women

were organized; trips, dinners, and dances were initiated along with an

eight-day festival called Israelite Festival Week. Cohen Levi trained many men

and women in his tradition. His most brilliant protégé is Cohen Michael Ben

Levi. Though not related by birth, the children of these men are related by

marriage. Cohen Michael was a rising star in the congregation from his youth.

Not only was he a loyal student and captivating speaker, he distinguished

himself academically by earning a B.A. and Master’s degree from City College in

New York. In 1978 Cohen Michael traveled to Guyana, South America, were he

began to establish an Israelite community based on the teachings of Cohen Levi.

While the community had always thought of immigrating to Israel, Cohen Michael asserted

that our mission was to “awaken Israelites to their true identity all over the

world.” He argued that Guyana would be a fruitful place for expansion and Cohen

Levi supported his efforts. In 1997, Cohen Michael published a book entitled Israelites

and Jews: The Significant Difference. Many of Cohen Levi’s children have

followed in his footsteps, but his son Cohen Shetmeyah Levi has exhibited the

most promise working in Guyana and now leading a congregation in North

Carolina.

Ironically, as Hashabah was expanding internationally its

base in Brooklyn, New York, began to contract significantly. When asked what

caused the decline, no one could identify a single event. It was as if the

entire climate was changing and indeed it was. The 1960s were over and with it

the “marvelous new militancy” that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr admired was being

replaced with economic despair. In Black communities across America interest in

history and religion were giving way to drugs, sex, and disco. Cohen Levi tried

to provide a bulwark against these forces; he tried to maintain high moral

standards, but in some ways the seeds of destruction were already planted.

Prince Tsippor Ben Zvulun was one of the lead drummers in Hashabah at the time.

As he described it, “many of us were losing our way.” He candidly admits that

he took wives in a casual manner and when Cohen Levi attempted to reprimand him,

he left the congregation like other young men. He joined B’nai Zaken which was

spiraling out of control by this point and drug use (and drug dealing) were

tolerated and sometimes celebrated as expressions of freedom from “the man”.

When Prince Tsippor emerged from this fog to start Sh’ma Yisrael he had a

greater appreciation for his teacher and mentor.[14]

After Hashabah lost is building on Belmont Avenue it enjoyed

a brief revival during the 1980s in Queens, New York, on Linden Boulevard just

a few blocks from Rabbi Levi Levy’s second congregation, Beth Elohim Hebrew

Congregation. Cohen Levi was the titular leader of this “new” Hashabah. His

teaching had not changed but many of the old members had not made the

transition to Queens, which required taking a train and bus by public

transportation. On the other hand the congregation had a new governing board

that was heavily represented by members of Cohen Michael’s family. They worked

together very well and brought lots of energy and enthusiasm which had been

missing. However, in a tragic twist of fate the building proved structurally

unsound and required more repairs than initially anticipated. Alternatively,

some members of this group concluded that it would be wiser and more productive

to continue their work in North Carolina or in Guyana. Many of those who

remained in New York desired a formal merger with B’nai Adath, the place of

their origin. The merger failed to occur for a variety of reasons on both

sides. Yet, much of Hashabah was, in fact, absorbed into B’nai Adath. Following

the death of Rabbi Yisrael, Rabbi K. Z. Yeshurun became the spiritual leader of

B’nai Adath, he enjoyed a very amicable friendship with Cohen Levi. Following

the death of Rabbi Yeshurun in 2008, his nephew, Rabbi Baruch Yehudah became

spiritual leader. Under his leadership the congregation seems to have found a

happy balance between its rabbinic traditions and Cohen Levi’s teaching.

During the final years of his life Cohen Levi became more

reclusive, making rare appearances at B’nai Adath or Sh’ma Yisrael. As the

effects of advanced age more pronounced, only family members and close friends

were allowed to see him. Following his death on July 24, 2014, the family

requested a private service conducted by Cohen Michael.

May 27, 1927 – July 24, 2014

[1]

It is standard academic practice to capitalize the names of national, ethnic,

or religious groups (German, Polish, Hindu) and to lower case the names of

racial groups (white, black, etc). I hold to the belief that races are not

biological categories but political constructions that should be treated like

ethnicity or nationality. Therefore, White and Black are capitalized just as

African American and Jew—since in most cases the terms are used synonymously.

[2]

United States Federal Census 1930

[3]

Professor Y’sudah Yehudah, interview by Rabbi

Sholomo Levy, 3 August 2014.

[4]

United States Federal Census 1940. The document indicates that they had been

living at this address for at least five years. His mother, Ella, is listed as

the married head of household but her employment status is given as unemployed.

[5]

Official obituary of Cohen Levi Yisrael prepared by his family.

[6]

Rabbi Hailu Paris, interview with Rabbi Sholomo Levy; and Biography of Rabbi

Yisrael

[7]

Rabbi Baruch Yehudah, the current spiritual leader of B’nai Adath, has written

an excellent history of the congregation. http://bnai-adath.com/about-us/67-2/

(13 August 2014).

[8]

At that time Rabbi Levi B. Levy was known as Lawrence McKethan. In 1967 Beth Shalom

would move to its current home at 730 Willoughby Ave, which was formally Young

Israel of Williamsburg. Similarly, B’nai Adath would move to its current home

at 1006 Green Avenue, which was formally B’nai Jacob Joseph. Both buildings had

been Ashkenazi synagogues with grand sanctuaries.

[9]

Chief Rabbi Levy, interview by Rabbi Sholomo Levy

[10]

From all of his marriages Cohen Levi produced 26 children. Three of his wives

preceded him in death. The names of all the children are listed in the official

obituary.

[11]

Professor Y’sudah Yehudah, interview by Rabbi Sholomo Levy, 3 August 2014.

[12]

Navi Tate would later become a rabbi

[13]

Prince Zurishaddai interview with Rabbi Sholomo Levy 14 August 2014. Prince

Zurishaddai explained that the attack on Hashabah was not ordered by Prince

Yaachov, who had relocated to Chicago. He also maintains that in B’nai Zaken

garb was not a mere matter of fashion, but individuals had to earn the right,

rank, or privilege of wearing turbans or certain types of jewelry. For example,

only married women wrapped their heads to distinguish them from eligible women.

The Chicago would subsequently moderate it views and merge to form a new

congregation under the leadership of Rabbi Capers Funnye called Beth Shalom

Bnai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation.

[14]

Prince Tsippor Ben Zevulun, interview with Rabbi Sholomo Levy, 2 August 2014.

Polygamy did not cause the downfall of Hashabah, but many of the men and women

I have interviewed—including some of the children of Cohen Levi—believe that

the practice contributed to the instability of the congregation and the breakup

of many marriages.